Often, clients believe (or have been told) that they need to improve their "listening skills" and ask for help on how to do that.

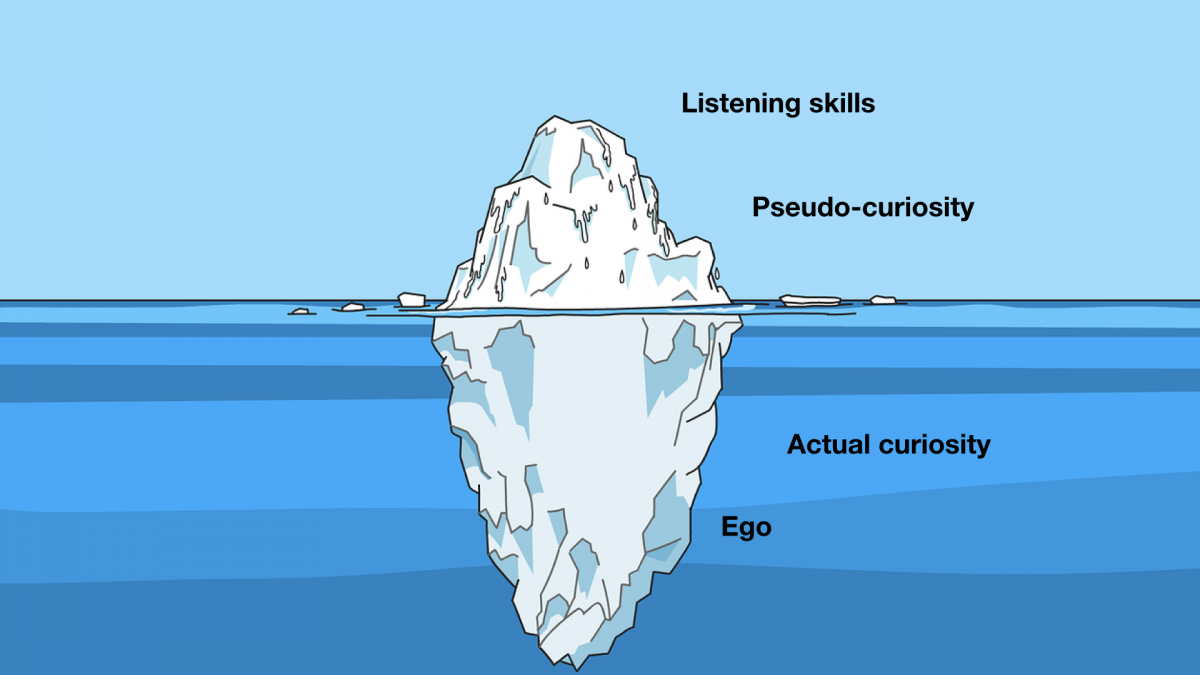

However, I've come to believe that listening skills that don't sit firmly on a foundation of true, actual curiosity are unlikely to be helpful - either they will "successfully" give an illusion that one is listening well, only to be followed by disappointment when it becomes apparent that this wasn't the case; or, more likely, it will become obvious quite quickly that there isn't a real curiosity behind questions that are being asked.

So, to be perceived as listening well, we need to sound curious. And to sound curious, we need to become and stay curious - sometimes (especially?), even when what we are hearing doesn't make sense to us. It is often useful to wonder (and ask) "what are you seeing that I'm not seeing?" and "what am I seeing that you might not be seeing?"

However, there is often an obstacle to being truly curious - our ego. How can we be truly curious if there is a chance that we will hear something that causes us to realize that our previous position was sub-optimal or even incorrect, if our ego is too uncomfortable with that possibility? How strongly do we feel the need (even if not consciously) to be "right"? And, if we are using technical "listening skills" (e.g., "ask open ended questions") at best this is likely to come across as pseudo-curiosity, as though we are trying to "sound" curious rather than being curious.

So, and this is one of those things that is often easier said than done, can we exercise our ego "muscle" that accepts others seeing useful things that we don't, having useful interpretations of things that differ from our interpretations and even having more useful answers (or steps toward answers) than we do? Perhaps, we can practice using Jennifer Garvey Berger's question "And how might I be wrong about this?".

If others are looking at exactly the same data points that we are and interpreting the data exactly as we are, isn't it likely that they will come to the same conclusions that we do? So, if we disagree, or want to find out if we disagree, being curious about what others are seeing and how they are interpreting it is likely to help us understand how they got to their position and why it is different to our position. Not only are we likely to understand others better, but they are more likely to feel that we are understanding (or, at least, trying to understand) them.

To listen well and for others to feel that we are hearing them, we need to be truly curious. And, for us to be truly curious, we need to be able to get our egos and our need to be "right" out of the way.